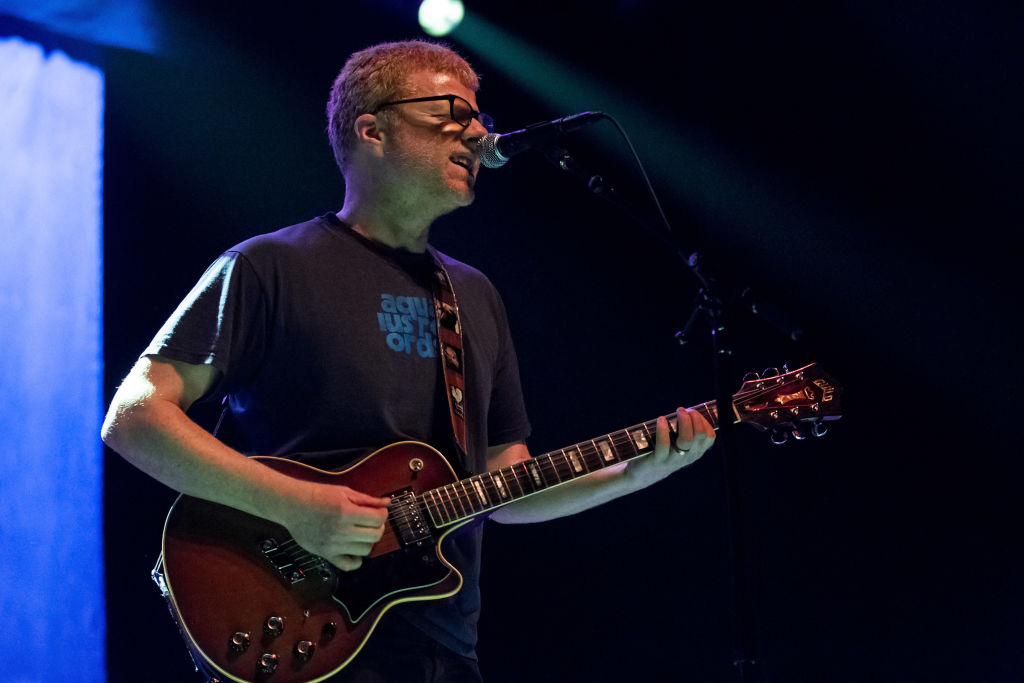

Today’s newsletter is a video interview I did with Carl Newman of the band The New Pornographers. Below is a transcript, edited for length and clarity. Enjoy! —Parker

Parker Molloy: Welcome to The Present Age. I'm Parker Molloy. Today, I'm excited to be joined by singer-songwriter Carl Newman, aka A.C. Newman, frontman of The New Pornographers and a solo artist whose work has shaped indie rock for years. In addition to his music, Newman has recently launched a Substack newsletter called Ballad of a New Pornographer, where he shares new songs, explores the creative process, and takes fans on a behind-the-scenes journey from idea to finished track. We'll be talking about what inspired his new project and how he navigates the balance between fun and madness in his songwriting. Carl, welcome.

Carl Newman: Hey, thanks for having me.

I'm excited to have you! For years, I had this really crappy MP3 player that whenever it would start playing, it would start playing your music, because it started with an A. So every single time I'd get into my car, I would hear just the opening drums of “Miracle Drug,” kind of that little beat.

You know, it's funny. I met Paul Rudd once years ago and he told me the same thing. Every time he turned on his car, it would be like, and I thought, That's cool. You know I exist.

And a much more embarrassing version of that story is years ago, I was DJing and I guess I had two iPods or whatever. Anyway, one of them started playing accidentally in the same way. And so I was DJing and I played my own song. “Miracle Drug” started playing and I had to just let it go. I had to go, “Yep, that wasn't a mistake. I meant to do that. I'm so confident in my own music that when I'm trying to get the party going, I put on my own music. Yep. I didn't mean to play Giorgio Moroder. I meant to play my own song.”

So tell me a bit about Ballad of a New Pornographer. You're actually the second member of your band that I know of that has a substack after Neko Case's Enter the Lung.

What do you want to know about it? Honestly, I don't even know anything about it yet. It feels kind of conceptual at this point. All I know is that I didn't want it to seem like all the other Substacks—maybe that's what everybody says. So I think I'm going to have to develop it and try to find my voice. Right now, I want it to be very music-centric. I don't think anybody needs me to do a lot of "Dear Diary" posts. Occasionally I will if something interesting is happening.

And it might be interesting if it's me complaining about my son's teacher—like, what's her problem? Why doesn't she get into a different field? I don't know, but does anybody really need to read that stuff?

You never know what people are going to be into.

So before I started it, I thought to myself, okay, this is going to be a lot of work, but I liked the idea of forcing my hand, being compelled to be creative. I liked the idea that—I'm not there yet—but at some point, I might think, "What am I going to post? I've got nothing to post." Then I'll go into my studio and say, "Well, do something. Start recording a song." It doesn't have to be finished; just do something. Or something that will make me go into all my unfinished songs and think, "Finish this."

One issue I have—I don't know if it's a very common thing—but I have so many unfinished songs that I've begun to wonder if I'm going to get them all out before I die. That's an honest thought I'm having. And I thought, if I'm only releasing ten songs every year or two, I'm never going to get them all out before I die. So I thought, I've got to figure something else out here.

I thought this would be a good spot for it. Also, I want to retrain my brain to be less of a perfectionist. Just tell yourself to put it out there. It doesn't even need to be the definitive version. You just put it out there and say, "There it is." Maybe I'm going to rewrite it, maybe I'll change the lyrics, maybe I'll toss out everything and just keep the lyrics. But I thought, okay, maybe that's interesting. Maybe for someone who writes music, it's an interesting glimpse into the process. You can do it for 20 or 30 years and still not feel like you know what you're doing.

I would never pretend to think I could ever teach anybody how to write songs, but you can hopefully help someone by just showing them things that you do. Like, sometimes your song isn't good, and you've got to toss out everything that doesn't work. Sometimes the only thing left is the drumbeat, or sometimes the only thing left is one line.

You mentioned finding that balance between creativity and madness where you're trying to get ideas flowing and you're always second-guessing yourself but knowing when to stop. Knowing when a song needs another idea or when you need to start subtracting ideas. Maybe it's got too many ideas; maybe everything you need is there, and you just need to take the lawnmower or the weed whacker to it.

So why did you decide to go with Substack instead of Patreon or just posting on a YouTube channel or something like that?

Well, I talked to Neko about it. I think I never really thought about it until I talked to her. She seemed to be happy doing it. Then I connected with one of the guys at Substack, Dan Stone, and I talked to him. He seemed very cool because I had questions. I think I told him vaguely what I wanted to do because one of my questions was, is it just writing? What if I wanted it to be a place where I posted music more? People think of Patreon as more a place to do that, or maybe, like you said, YouTube. But he said, no, people do that. We went through various people's Substacks—he showed me Jeff Tweedy's and Kevin Morby's and a few others.

I have so many unfinished songs that I've begun to wonder if I'm going to get them all out before I die. That's an honest thought I'm having. And I thought, if I'm only releasing ten songs every year or two, I'm never going to get them all out before I die. So I thought, I've got to figure something else out here.

The Substack that really fascinates me is George Saunders's. I'm fascinated when one of your favorite writers is giving you writing tips. To me, that feels kind of priceless. And I thought, okay, I'd like to find more of those. Does David Mitchell have one of those as well? Does Murakami?

Yeah, there's one that I read that's really interesting for writing tips that is completely not applicable to anything I do, though—it's Chuck Palahniuk's. His is really interesting, his Substack. But the same kind of idea where you're getting writing advice from someone who is very good at it. But I guess that's kind of what you're doing with music.

Yeah, I mean... I don't know. I would hope so. But like I said, I would never pretend that I could teach somebody how to write a song. I don't think anybody wants me to be their songwriting teacher because I would be the person listening to their song and saying, "Well, you should just scrap it and start again." Also, I don't know. I can only tell you about a very specific kind of songwriting. Like, I was just thinking of it—who's the hip-hop artist who did "Turn Down for What"? You know, the Daniels did the video?

Yeah, Lil Jon.

To me, that's brilliant, but is it songwriting? To me, it seems more like avant-garde art—massively popular avant-garde art. If someone came to me and was trying to do that, I would say, "Yeah, keep doing that, but I can teach you nothing. I have no advice for you."

I guess if someone likes what I do, then yeah, I can tell you things I do that help me write. But the sad part is that I go into every song feeling like I don't know how to do this. And what's worse is I want it that way because I feel like if I'm writing a song and it feels like something I know how to do, and it's coming easy, I think to myself, "What is the point? Why am I just spinning my wheels here?" I mean, I'd probably be making much more money if I thought that way, but I'm always kind of disappointed in myself when it sounds like me because I'm trying not to.

So you described your songs as being the sum of many different ideas pulled from the air as they pass by. I'm kind of curious: how do you decide what ideas stay and what go in a song? Is it just what works for you? What sounds good?

I don't know, because sometimes you make the wrong choice. There's a song I just finished—I can't talk about it because nothing's been announced yet—but we were mixing it, and we basically mixed it. And I thought, "Something's not right here. Something's bugging me about this song." I went back into older versions of it, versions from six months earlier, and I realized I had it six months ago. I had it completely nailed, but I just moved past it. I moved past it and changed the chorus. I was like, "Why did I change the chorus?" I changed the bass line; I changed so many things. It was there. What's wrong with me?

I think that is a problem. Sometimes you have it, and you just keep going. You don't know where to stop. Like the person who's painting and doesn't stop until it's just a pure black canvas—it's like, "I've added every color." It's hard to learn that lesson.

Another big lesson is trying to figure out when to listen to yourself and when to listen to another person. I guess that's being a good judge of character. Sometimes you've got to think, "Well, this person's an idiot. I shouldn't listen to them." And then, "I respect this person, so I'm going to listen to them." But also, sometimes the maddening part is only you know the solution to your problem. When you're writing a song, you're asking a question; you're building this puzzle that only you can solve. Sometimes you look outside for help to get you through this maze, but sometimes you realize, "Okay, this is mine. This is mine to solve." Other people don't know how to solve it; only I know how to solve it. Like I said, it's a road to madness.

And speaking of madness and chaos and all of that, you did say that the sweet spot of your creative process is somewhere between fun and madness. What do you mean by that?

Well, I guess for me, it's fun to just throw everything at a song. Sometimes I just don't know what it should be. Is it a ballad? Should it be a really minimal song, or should it have a lot of orchestration? Finding that can be fun. But also, like I said, sometimes you go past it. You just keep working, and you realize, "No, I'm making it worse." Then you start getting bummed out. It's like, "Why am I making it worse? What's wrong with the song?" That's when you have to dial it back and realize, "Okay, maybe you're going slightly crazy. Maybe you need to take a break and step away from it and then listen a little while later."

But yeah, I think sometimes it is kind of linked to mental illness. I think I have a lot of anxiety, which means my brain is moving very quickly, and it's not always moving in a very effective way. Sometimes ideas are flying through my brain, and some of them are musical, and some of it's good. If I can catch all the ideas and put them in order and work on them, I can use all those thoughts to do something good. But if I don't, it can just lead to anxiety. It's just a mess of thoughts; I have no order. So I think that's what I'm ultimately getting at. If you're a psychologist or a psychiatrist and asking what I meant by the balance between fun and madness, I think it's that.

And you also mentioned that your Substack could be the only place where some of your new music will be available. What led you to that decision? Was that just as you were saying earlier about trying to get so many songs out there in such a limited amount of time?

Yeah, I mean, I think so. Obviously, I don't want to bypass the record label—I love Merge—but I even like the idea that maybe there's a solo project, whatever form it would take, whatever the name would be. And maybe Merge would want to put it out, but maybe I'd say, "Hey, I'll pay for it. You don't have to give me any kind of advance, but I just want to sell it through my Substack." Maybe they'd want to do that.

I like the idea of it just being something kind of cool, kind of exclusive. When you're doing anything, you want it to be something that you can't get anywhere else. You don't want it to be just more of the same. So I thought, okay, that would be cool if I put out a record and there were only 500 copies or a thousand copies, and I said, "You can only get it here." And I wasn't concerned about making money; I was just concerned about getting music to the fans. I'm assuming the people who are paid subscribers of my Substack are fans—I don't know any other way to describe them.

So I like the idea of saying, "Here, here's a reward for being a fan. I will give you something that you can't get anywhere else." I like the idea of it being kind of like an old-fashioned fan club. I feel like when I was a kid, there was stuff like that. The Beatles used to make those Christmas singles that only the fan club got. I love that kind of stuff. And I'm sure people are doing that right now—I don't know who.

But yeah, I like it. I mean, it's a lot of work, but that's what I signed up for. I feel like I just got a job, actually. Do you know that Daniel Johnston song "First Day at Work"? It kind of reminds me of that. The boss is being nice to you, but that's just for today. It's your first day at work. You feel like a jerk.

Yeah.

I feel like I'm just a few days into Substack, but soon everybody's going to say, "Okay, pick it up. Learn how to do this." You only get to be a beginner for so long. Now I have to figure out how to keep it interesting. But it's kind of fun.

Sure.

It's a good way to procrastinate, too. I have a lot of work to do around the house, and I get kind of overwhelmed—painting and staining and sanding. This morning I thought, "Why don't you record a song from *The Slow Wonder*? Since the tickets for your tour are going on sale today, why don't you record 'Drink to Me, Babe, Then' and just play it and then post it?" It ended up taking me a few hours because I'm a Luddite, and like I said, it's my first day at work, and I feel like a jerk. I had to figure out how to post a video and things like that. But it was fun to get up in the morning and think, "Okay, what am I going to do today? What am I going to try and do? I'm going to try to do something interesting—or if not interesting, well, at least something."

On that note, thanks so much for your time. Everyone should go subscribe to Ballad of a New Pornographer. Thank you so much, Carl.

Yeah, if you subscribe, you can buy the reissue of my album, and then maybe you can just sit on it for a year and resell it. Just make sure to keep it in mint condition, and maybe—what do you pay for it? Twenty-five? Maybe you can sell it for fifty in a couple of years. I don't even want people to open it; I'm thinking of it more as an heirloom.

Okay. There you go. Buy this investment. This is investment advice. [editor’s note: not actually investment advice]

Yeah, a good investment. What do they call that—return on investment? There's a word for it. Get a good return on your investment. It's better than crypto.

Yeah, exactly. Cool. It's better than crypto. I think that should be it: “The Slow Wonder”: It's better than crypto. There's your tagline.

Yes.

It's a low bar, but you crossed it.