Now Everyone's Saying 'Oh, Good'

Trump told the media exactly how they'd cover his Greenland threats. They did it anyway.

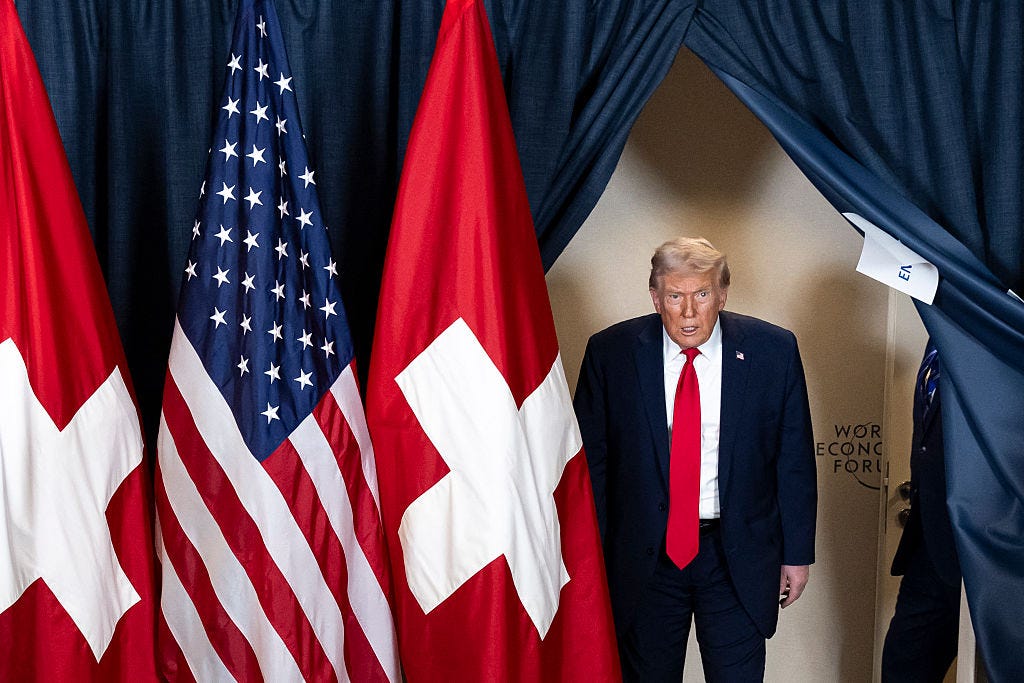

On Wednesday, Donald Trump addressed the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. During his speech, he had this to say about Greenland:

“We never asked for anything and we never got anything. We probably won't get anything unless I decide to use excessive strength and force where we would be frankly unstoppable. But I won't do that. Okay, now everyone's saying, ‘Oh, good.’ That's probably the biggest statement I made because people thought I would use force. I don't have to use force. I don't want to use force. I won't use force. All the United States is asking for is a place called Greenland where we already had it as a trustee, but respectfully returned it back to Denmark not long ago after we defeated the Germans, the Japanese, the Italians, and others in World War II.”

Read that again. Sit with it for a second.

The President of the United States just told a room full of world leaders and business executives that American military force would be “frankly unstoppable” against European allies. And then he said he wouldn’t do it. For now.

You won’t find this in any diplomacy textbook. It’s the language of a protection racket.

So how did reporters cover it?

NPR (original headline): “Trump says ‘I won’t use force’ to obtain Greenland in Davos speech”

ABC News: “Trump rules out using military force to acquire Greenland in Davos speech”

CNBC: “Trump calls for ‘immediate negotiations’ on Greenland, but rules out using force”

If you only read those headlines, you’d think the president made some kind of conciliatory gesture. A de-escalation, even. “Oh good, he’s not going to invade Denmark. What a relief!” The stock market certainly interpreted it that way, rallying on the news that the American president had taken military action against a NATO ally off the table.

But that’s not what happened in that room. Trump reminded everyone of his capacity for violence, made clear that resistance would be futile, and then offered them a chance to surrender peacefully. “I won’t use force” is misdirection, and the coverage fell for it.

Think about what he actually said. “We probably won’t get anything unless I decide to use excessive strength and force.” That “unless” is doing a lot of work. It’s a conditional. It means: if you don’t give me what I want, the “excessive strength” option remains available. The reassurance that follows doesn’t negate the threat. It completes it.

And there was another line in the speech that barely registered in most stories. Addressing the European leaders who have opposed his Greenland push, Trump said: “You can say yes, and we will be very appreciative, or you can say no, and we will remember.”

We will remember.

He’s threatening countries that have been American allies for 80 years, on a global stage, and daring them to do something about it.

And just in case the implications weren’t clear enough, Trump took a moment to remind the audience of what he’d just done in Venezuela. “We’re a great power, even greater than many thought. They found that out two weeks ago in Venezuela,” he said. Telling European leaders to hand over territory while referencing your recent military actions in the Western Hemisphere is making an offer they’d be wise not to refuse.

CBC’s coverage was blunt about the nature of the speech, describing it as “at times menacing and at times rambling.” That’s closer to accurate. But “menacing” didn’t make it into most American headlines.

This is what sanewashing looks like. You take a threat, you extract the denial, and you print the denial as if it were the news. “Trump won’t use force” is technically a thing he said. But printing that without the “unstoppable” part, without the “we will remember” part, without the Venezuela reference, doesn’t just fail to inform readers. It actively misleads them about what happened in that room.

Trump called his shot

There’s a moment in the Davos speech that deserves special attention. It’s easy to miss if you’re not looking for it, buried as it is in the middle of the threat-then-denial sequence. But it’s the most revealing thing Trump said all day.

“Okay, now everyone’s saying, ‘Oh, good.’ That’s probably the biggest statement I made because people thought I would use force.”

He narrated the sanewashing as it was happening. In real time, from the podium, Trump described exactly how journalists would cover his remarks. He knew they’d seize on the denial. He knew “I won’t use force” would become the headline. He knew the threat would fade into background noise. And he said so, out loud, while the cameras were rolling.

This wasn’t an accident or a verbal stumble. Trump was telling the room, and the reporters in it, that he understands how this game works. Make the threat vivid enough that everyone hears it, then give them a clean quote they can print without feeling like they’re taking sides. The threat does its job. The denial provides cover. Everyone gets what they need.

The coverage, almost universally, followed the script he laid out for them.

I’ve been writing about sanewashing for a couple of years now. The term describes what happens when journalists take incoherent, threatening, or unhinged statements and repackage them into the conventional language of political reporting. It’s how “they’re eating the dogs” becomes “Trump raises concerns about immigration.” It’s how an hour of rambling about sharks and Hannibal Lecter becomes “Trump holds rally in Las Vegas.”

But this is something slightly different. Trump isn’t just benefiting from sanewashing; he’s anticipating it. He’s building it into the structure of his rhetoric. The denial isn’t a softening of the threat; it’s the delivery mechanism that ensures the threat travels through mainstream news coverage without being flagged as dangerous.

Consider the irony: Trump delivered a line that explicitly mocked the predictability of media coverage, and then media coverage proved him right. He told them they’d say “Oh, good,” and they said “Oh, good.” He might as well have written the headlines himself.

It suggests something a lot of reporters don’t want to confront. Trump, for all his incoherence on other subjects, has a sophisticated understanding of how political journalism works. He knows the conventions. He knows that reporters want clean quotes. He knows that editors want headlines that don’t sound editorialized. He knows that “Trump threatens force” will get flagged by cautious copy desks, while “Trump says he won’t use force” sails through. So he gives them both, in the same breath, and lets the machinery of neutral-tone journalism do the rest.

The weeks before Davos

To understand what Trump was really doing in that speech, you have to look at what came before it. The Davos address didn’t happen in a vacuum. It was the culmination of weeks of escalating threats, each one a little more explicit than the last.

Earlier this month, at a White House event ostensibly about oil companies and Venezuela, Trump offered this regarding Greenland: “We’re going to do something on Greenland whether they like it or not, because if we don’t do it, Russia or China will take over Greenland. That’s what they’re going to do if we don’t. So we’re going to be doing something with Greenland, either the nice way or the more difficult way.”

Soon after, he sharpened the language: “I would like to make a deal the easy way, but if we don’t do it the easy way, we’re going to do it the hard way.”

The easy way or the hard way. We heard the same phrase from Trump’s own FCC chair, Brendan Carr, back in September. When the administration went after late-night host Jimmy Kimmel, Carr appeared on a far-right podcast and mentioned his agency’s role in granting broadcast licenses. “When we see stuff like this, look, we can do this the easy way or the hard way,” he said. Even Ted Cruz described the remark as similar to the language of organized crime.

So when Trump stood at Davos and said he “won’t use force,” he was saying it after weeks of promising to do things “the hard way” if necessary. The denial was arriving long after the threat had been delivered, repeated, and amplified.

And the threats weren’t just rhetorical. In the days before Davos, Trump announced new tariffs on eight European countries specifically because they had opposed his Greenland demands. Economic punishment was already underway. The squeeze had begun. By the time Trump told the Davos audience that America would be “unstoppable” but he wouldn’t use force, the coercion was already in motion through other channels.

This is how the shakedown works. You don’t walk into someone’s business and immediately start breaking things. You send signals first. You make clear that you’re willing to cause pain. You demonstrate, through smaller acts of aggression, that you’re serious. Then, when you finally sit down to “negotiate,” the violence is already implied. You can afford to sound reasonable because everyone in the room knows what happens if they say no.

Trump told the Norwegian prime minister in a message that the world would not be safe until America had “Complete and Total Control of Greenland.” He reposted content on social media casting the UN and NATO as the “real threat” to the United States, rather than China and Russia. He threatened tariffs. He invoked Venezuela. He promised to do things “whether they like it or not.”

Then he went to Davos and offered to negotiate.

Headlines treated this as a pivot toward diplomacy. But diplomacy requires good faith, and there was no good faith here. There was pressure, escalation, and then a momentary softening of tone designed to look like an off-ramp. European leaders in that room understood this. Emmanuel Macron spoke the day before about a shift toward “a world without rules,” where “international law is trampled underfoot and where the only laws it seems to matter is that of the strongest.” He said, “We do prefer respect to bullies.”

Denmark’s foreign minister, responding to the speech, said it was “positive” that Trump ruled out military force but added that “the challenge is still there” because “the president’s ambition is intact.” A foreign minister from a NATO ally was publicly expressing relief that the American president said he wouldn’t invade, while noting that the threat of annexation remains. This is where we are.

Canadian Prime Minister Mark Carney, in his own Davos speech, laid it out plainly: “We are in the midst of a rupture, not a transition.” Trump’s response, later in his own address, was to turn to Carney’s remarks directly: “Canada lives because of the United States. Remember that, Mark, when you make your statements.”

Same language, same strategy. Reporters keep covering each incident as if it’s a one-off, an aberration, a moment of Trumpian excess that will soon give way to normal diplomacy. Meanwhile, the approach just keeps repeating.

A specific kind of language

The Davos speech would be alarming enough on its own. But it becomes something else entirely when you recognize it as part of a rhetorical style that stretches back years. Trump has been talking this way since he entered political life. Journalists keep treating each instance as a novelty, a gaffe, a moment of Trump being Trump. What they’re missing is the consistency of the technique.

Trump talks like a mob boss.

I’m describing a specific rhetorical style, one that has been analyzed by linguists, prosecutors, and organized crime experts. It has identifiable features: indirect speech acts, conditional threats, coded language, and plausible deniability built into the structure of the communication itself. The speaker makes the threat clear to the intended target while leaving themselves room to claim, if pressed, that they never actually said what everyone understood them to mean.

Michael Cohen, Trump’s former personal attorney and fixer, explained this during his 2019 congressional testimony: “He doesn’t give orders. He speaks in code. And I understand that code.”

James Gagliano, a former member of the FBI’s organized crime squad, said on Twitter that he “couldn’t begin to number” the cooperating witnesses who described orders from mob bosses using similar language. The phrasing Cohen used to describe Trump’s communication style was, to Gagliano, immediately recognizable from his years investigating the Mafia.

As Henry Farrell wrote in The Washington Post, there’s a reason mob bosses prefer ambiguous language: it makes it harder to prove charges against them. If you say “kill him,” that’s evidence. If you say “take care of the problem,” you’ve communicated the same instruction while maintaining the ability to claim you meant something else. The structure protects the speaker.

Trump learned this dialect early. His mentor for years was Roy Cohn, the infamous attorney who represented major mob figures. The late Selwyn Raab, a New York Times reporter who covered organized crime for decades, described Cohn’s essential lesson: “Always be aggressive, take no prisoners.” Trump absorbed that in the New York construction world of the 1980s, an industry thoroughly entangled with organized crime. He built his business in an environment where the coded language of threat and implication was simply how deals got done. And when he moved into politics, he brought that vocabulary with him.

James Comey, who spent years as a federal prosecutor going after the Gambino crime family before becoming FBI director, recognized the style immediately. When Trump invited him to a private dinner at the White House in January 2017 and demanded “loyalty,” Comey later compared the encounter to “Sammy the Bull’s Cosa Nostra induction ceremony.” Comey wasn’t being hyperbolic. He was describing what he saw.

The receipts

Line them up and the structure becomes impossible to ignore.

July 2019: “I would like you to do us a favor though”

The call with Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky became the basis for Trump’s first impeachment. The White House released its own summary, apparently believing it would exonerate Trump. It did the opposite, if you knew how to read it.

Zelensky, whose country was fighting a war against Russian-backed separatists, brought up Ukraine’s need for American military support. “We are almost ready to buy more Javelins from the United States for defense purposes,” he said.

Trump’s response: “I would like you to do us a favor though.”

That “though” is doing all the work. As one analysis noted, the word functions grammatically to place a condition on what came before. You want missiles? I have a favor though. The favor was investigating Joe Biden, Trump’s likely opponent in the 2020 election. Trump had frozen nearly $400 million in military aid to Ukraine roughly a week before the call. The transaction was right there on the page.

Intelligence Committee Chair Adam Schiff called it “a classic Mafia-like shakedown.” But a substantial portion of the coverage focused on the absence of an explicit quid pro quo statement. Because Trump didn’t say “if you don’t investigate Biden, you won’t get the missiles,” many outlets treated the extortion as ambiguous. This is the sanewashing trap: demanding literal confession while ignoring structural coercion.

January 2021: “I just want to find 11,780 votes”

The call to Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger, recorded and released by The Washington Post, was Trump at his most explicit. The election was over. Biden had won Georgia by 11,779 votes. The results had been certified. And Trump called up the state’s top election official to demand that he manufacture a different outcome.

“All I want to do is this. I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have. Because we won the state.”

As legal analysts pointed out, Trump wasn’t asking Raffensperger to investigate fraud. He was asking him to produce a specific number of votes that didn’t exist. The word “find” suggests creation, not discovery.

But it was the threat that followed that made the call unmistakable. Trump told Raffensperger that failing to act would be “a big risk to you and to Ryan, your lawyer.” He explicitly suggested that Raffensperger could face prosecution for not going along: “That’s a criminal offense. And you can’t let that happen.”

Much of the coverage centered on whether Trump genuinely believed he had won. This framing turned an act of extortion into a psychological curiosity. Whether Trump believed he won is irrelevant to whether he tried to coerce a public official into falsifying election results.

2018-2019: “Rat” and “Watch father-in-law”

When Michael Cohen began cooperating with federal investigators, Trump launched a public pressure campaign using language that could have come straight from a mob movie.

He called Cohen a “rat“ repeatedly on Twitter. In ordinary usage, a person who exposes wrongdoing is a whistleblower or a witness. In organized crime, they’re a rat. Then came the threat: Trump tweeted about Cohen’s father-in-law, suggesting investigators should “take a look” at him. Keep talking, and your family will suffer consequences.

Cohen delayed his congressional testimony as a result, with his lawyer explicitly citing “ongoing threats against his family from President Trump.” The witness intimidation worked, at least temporarily. Media coverage framed these episodes as “Twitter feuds” or “Trump lashing out.” Just another day, just another tweet.

Same technique every time. State the threat, build in the deniability, let the target understand what you really mean while giving reporters enough ambiguity to write a “balanced” story. It worked on Zelensky. It didn’t work on Raffensperger, but only because he refused to play along. It worked on Cohen, at least for a while.

And it’s working now, on Denmark and the European allies who heard “we will remember” and understood exactly what that means.

Why this keeps happening

If you’ve read this far, you might be wondering how this is still possible. Trump has been a public figure for decades. The “mob boss” framing has been written about extensively. Prosecutors, former FBI directors, linguists, and organized crime experts have all pointed to the dynamic. And yet, every time Trump delivers another threat wrapped in a denial, newsrooms dutifully print the denial as the headline.

Part of the answer is structural. Journalism, as a profession, is biased toward coherence. When a reporter covers a speech, their job is to produce a story that makes sense to readers. If a political figure rambles for an hour, veering between conspiracy theories, personal grievances, and the occasional policy fragment, the reporter can’t just transcribe the chaos. They have to find the signal in the noise, identify the “newsworthy” bits, construct a narrative. This is usually a good instinct. Most political speech benefits from distillation. But when the chaos is itself the message, when the incoherence and menace are the point, this filtering process becomes a form of distortion.

Kelly McBride at Poynter described one version of this problem: journalists have an impulse to make things easier for news consumers. That’s fine when you’re translating economic jargon from the Federal Reserve chair. It’s a disaster when you’re trying to make sense of something that was never meant to be sensible.

There’s also the fear of appearing biased and the sheer problem of volume. In a polarized environment, outlets are terrified of being accused of taking sides. Accurately describing Trump’s rhetoric as threatening or authoritarian invites accusations of partisan overreach, even when the description is factually supported by the transcript. So editors soften the language. Meanwhile, Trump says so many outrageous things that any single statement struggles to break through. A Media Matters study found that Hillary Clinton’s “deplorables” comment in 2016 received 18 to 29 times more coverage than Trump’s “vermin” speech in 2023, in which he pledged to “root out” political opponents who “live like vermin within the confines of our country.” One candidate’s verbal stumble became a defining campaign moment. The other candidate’s explicit dehumanization of his enemies barely registered.

Political scientist Brian Klaas has a term for this: “the banality of crazy.” Things that would be disqualifying scandals for any other politician have become background noise for Trump. Each threat that gets normalized makes the next one easier to dismiss.

And underneath all of this is a category error that newsrooms have never fully corrected. Political journalism is built to cover people who are operating within a shared framework of democratic norms. The conventions of the beat assume good faith: politicians may spin, they may exaggerate, they may mislead, but they’re fundamentally playing the same game as everyone else. Trump isn’t playing that game. He’s operating in a different register entirely, one where threats are leverage, where denials are cover, where the whole point is to communicate menace while maintaining deniability. When you bring a “both sides” framework to a protection racket, you end up printing the denial and burying the threat.

Michael Tomasky, in an interview with WBUR, made a point worth emphasizing: this is not a conspiracy. Reporters and editors are not colluding with Trump to make him look better. The sanewashing happens because the normal conventions of political journalism do not account for a candidate who refuses to operate within “a certain pattern and a certain norm.” The system is designed for a different kind of politician, and it breaks down when confronted with someone like Trump.

But the fact that the failure is structural rather than intentional doesn’t make it less damaging. Every headline that privileges the denial over the threat is a small act of misinformation. Every story that treats “I won’t use force” as the news, rather than “I reminded everyone that I could use unstoppable force,” contributes to a distorted picture of reality. Readers who rely on mainstream coverage encounter a version of Trump that has been sanded down, made palatable, rendered comprehensible within frameworks that don’t apply to him.

Meanwhile, anyone who watches the actual speech, or reads the full transcript, sees something entirely different. The gap between the raw material and the coverage is where the sanewashing lives.

For those who would like to financially support The Present Age on a non-Substack platform, please be aware that I also publish these pieces to my Patreon.

The audience that gets it

Here’s what’s striking about Davos: the people in that room understood what was happening. European leaders, diplomats, the foreign press. They didn’t need anyone to explain that “we will remember” was a threat. They didn’t need a linguistics professor to parse “unless I decide to use excessive strength.” They heard it. They reported it. They’re acting accordingly.

Carney called it a “rupture.” Macron talked about “bullies” and the collapse of international law. Denmark’s foreign minister had to publicly thank Trump for not invading. These are not people who saw the speech and came away reassured by the “I won’t use force” line. They saw through the denial to the threat beneath it, because that’s what the threat was designed to make them do.

The only audience that seems to keep getting it wrong is the American media, which continues to treat Trump’s words as if they were uttered by a normal politician operating within normal constraints. The international community is responding to reality. American headlines are responding to the version of reality that Trump has constructed for them, the one where the denial is the story and the threat is just color.

This gap has consequences. When allies start making contingency plans for a post-American world, when they begin building institutions that route around Washington, when they start treating the United States as a threat rather than a partner, American readers should understand why. But they won’t, if all they see is “Trump seeks negotiations.”

At Davos, Trump told reporters exactly how they would cover his speech. “Now everyone’s saying ‘Oh, good,’” he said, mocking the relief that would follow his pro forma denial. He predicted the sanewashing. He announced it. He practically dared them not to do it.

And then everyone said, “Oh, good.”

The kind of analysis you do is sorely needed in the current environment. Thank you so much for your work.

Thank you so much for what you do.