"Just here for the ratio!" vs. "Should auld acquaintance be forgot and never brought to mind?"

In the final newsletter of the year, I reflect a bit on internet culture, the social media incentives to "dunk" on others, and how I plan to approach 2022.

Earlier this week, as I sat mulling what I should write for my final newsletter of 2021, I spent some time reflecting on the state of internet communication (which is, you know, kind of a running theme of mine). The internet is a tool that can be used to improve the state of the world in tremendous ways that would have seemed like pure fantasy just a couple of decades ago. It provides us with a way to connect with people around the world, to open the doors of knowledge, and encourage global collaboration. It can help us join forces to fight common enemies like climate change and global pandemics. It can do so, so much good — and, to be entirely fair, it sometimes does. But lately, I’ve been stuck thinking about how rare those objectively good moments are and how plentiful the bad can be.

The Present Age is a reader-supported newsletter by me, Parker Molloy. There are free and paid subscriptions available, but the best way to support my work is to become a paid subscriber.

This year has been god-awful for my mental health, and while some people spend the waning moments of the current calendar’s lifespan affirming their beliefs that January 1 will mark a moment where things will magically turn around, but I can’t bring myself to do that anymore.

This year will be better than the last!

Okay. Sure. I mean, I’d love for it to be better than the last, but I just can’t get my hopes up, as much as I’d like to. I would love nothing more than to be proven wrong about this. Anyway, I see that I’ve digressed a bit... Where was I… ah! Okay, so…

As I was saying, the internet is a tool that can be used for so much good but is too often used to do the exact opposite.

Earlier this week, I was reading a comic at The Nib, titled, “Piled On,” by Mallorie Udischas-Trojan, whose work I’ve admired and appreciated for years (in 2017, I put together a post for Upworthy about some of the work she did about being trans on her Manic Pixie Nightmare Girls comic).

In her piece for The Nib, Mallorie wrote about the reaction to a comic she posted on April 8, 2020. The tl;dr of the April 2020 comic is that the main character walks into an art supplies store, loads her bag with pens and whatnot, then declares herself to be a criminal mastermind. “Be crimes, do gay,” Mallorie wrote for the Twitter caption, a play on the “Be gay, do crime” meme.

That day, someone posted her comic to 4chan’s /co/ (Comics & Cartoons) board along with the words, “New guy asshole made a new comic. Enjoy,” referencing one of her comics from a few months earlier that caused controversy because the main character laughed about a famous YouTuber getting robbed. Both the shoplifting comic and the “New Guy” comic have their own Know Your Meme pages.

Why am I telling you all of this? Because it helps explain how the shoplifting comic became controversial in the first place. People were looking for an excuse to pile on someone they already didn’t like because of a completely different comic she made (as well as the fact that she’s trans, which based on the archived 4chan thread, definitely played a role in the rage-y response), saw this, and essentially decided to pretend that they were extremely offended by the thought of a fictional character stealing from a fictional store being run by fictional employees.

A proper response to a comic like this with a message you disagree with might be to ignore it or to share that you didn’t like it. Instead, what she got was thousands of people rage-replying to the original post, quote-tweeting it to alert other people to it (so that they, too, could rage-reply), plus everything that came after.

As she explained in her comic for The Nib, the bad-faith criticisms from the 4chan types helped start a fire that would spread to Mallorie’s own circle of friends (see points number 3 & 4 in this guide to how a fake feminist hashtag went viral). While she admitted in the replies that as a teenager, she stole art supplies, that didn’t magically make her comic a promotion of shoplifting. Still, the response she got was wildly out of proportion, on par with what you would expect if a politician legitimately proposed implementing an annual Purge.

She went into detail about the effect that ordeal had on her health, her relationships, and her career. I highly recommend checking out the rest of that piece over at The Nib.

Coincidentally, the same day “Piled On” was published at The Nib, video essayist Lindsay Ellis announced on her Patreon page that she was walking away from making and publishing new content. Basically, what happened was that in March 2021, Lindsay tweeted, “Also watched Raya and the Last Dragon and I think we need to come up with a name for this genre that is basically Avatar: The Last Airbender reduxes. It’s like half of all YA fantasy published in the last few years.”

Here’s how Distractify explained the reaction:

Almost immediately following her comments, people began replying, arguing that her tweet suggested that Avatar, a show influenced by Eastern cultures, was actually the origin point for many stories that had Eastern cultural elements. Critics of Lindsay also pointed that Avatar's writers were white, while Raya had people of Asian descent on its writing team.

A couple of weeks after this, she posted a lengthy elaboration to her YouTube page (it’s an hour and 40 minutes long, so it really goes deep). If you go to the 01:11:13 mark, she spends about 5 minutes discussing the tweet, specifically.

Were there valid criticisms of what she tweeted? Sure. She acknowledged this at the time and more recently. Were there a lot of absurd/disingenuous/over-the-top criticisms, as well? Absolutely.

Here’s one paragraph from her Patreon post from earlier in the week (the post was briefly public before she put it behind the Patreon paywall, and if you’re a subscriber of hers, you can check the full thing out here):

2021 has been the worst year of my life. I am traumatized by it. To this day I still have people scolding me by how I handled it, that I should have handled it differently, that I should have “controlled” my “stans”, as if I had the capability to know what any of these people were even saying to strangers on Twitter while I was shitting blood for weeks on end. The worst thing about this whole year is that I can’t even admit this trauma because of all the rhetorical devices people have already come up with to dismiss it. That centering my own pain is evidence of me “not listening” (does it occur to these people that you can listen, and disagree with other people’s conclusions?) That I’m weaponizing my “fragile white womanhood” or whatever to point out that having thousands upon thousands of people who you have never met hate you and say whatever will get them the most updoots about is, in fact, traumatizing. That people I used to know would flagrantly lie about me on Twitter dot com to the tune of thousands of retweets and tens of thousands of likes, and I just had to sit there and take it. My favorite are the people who dismiss any potential harm I might have incurred as justified because I am a “wealthy, white woman” (I am not wealthy), while these same people’s hearts positively *bleed* for Britney Spears.

This edition of the newsletter isn’t about “cancel culture” and whether or not it’s real, but it is about something semi-related: proportionality and the internet.

One of the first interviews I did when starting this newsletter was with Michael Hobbes (you may know him from his writing, his former podcast You’re Wrong About, or his current podcast Maintenance Phase). We chatted a bit about the challenges of trying to cover difficult topics that require nuance … especially on social media. For instance, there was a really informative episode of You’re Wrong About that debunked some common myths about human trafficking and discussed how QAnon types have co-opted the anti-trafficking cause.

Here’s part of that exchange [emphasis added in bold]:

PARKER MOLLOY: One thing that I was wondering about, so the episode of You're Wrong About, that you did about human trafficking. Now that one thing I find really — because it was a really interesting episode, and I just find it really interesting, because it's something that people — no one wants to come off as being pro-human trafficking, obviously. Is that something you worried about when making that? That people are going to see that and just not get the nuance involved in saying that like, "No, this just isn't the ..." Yeah.

MICHAEL HOBBES: Yeah, and I mean, we've definitely gotten, it's not that many, but we've definitely gotten, I noted in there that this statistic of 40 million victims of human trafficking every year, that includes 15 million people who are victims of forced marriages. I have complicated feelings on that, but forced marriages are not what most people think of when they hear trafficking. They're imagining kids being kidnapped, they're not imagining kids in South Asia being married against their will, as part of this longstanding cultural tradition. That's just not what people think of. So I was trying to delineate those two things. Both of those things are bad, but it doesn't actually make sense to group children being kidnapped and arranged marriages in South Asia together. As if that's one problem, those have different causes and solutions.

Then of course I got the emails, like, "Wow, I was really disappointed to hear you say that forced marriages are good." I'm like, "Well, that's not my view, but some people are determined to take that meaning and whatever." But that's also, I mean, I do think that one of the things that's so interesting about public figure-dom, on the internet now, is just the sheer scale of the internet. We have a couple of episodes that have gotten more than a million downloads. And if 1% of our audience hates them, and thinks that we're pieces of shit, and we suck ass, and they want to email us, and flood our mentions or whatever, that's 10,000.

So if I got 10,000 emails saying like, "You're a piece of shit for this episode," I would probably assume that represented a huge portion of our audience. I would assume that like, "Oh my God, everybody who listened to the show, is really mad at me," when in fact that might actually just be 1% of the audience who was extremely vocal. And it doesn't actually represent the other 99% of people, but there's no way to tell. It doesn't feel like it's only 1% of your audience if you're getting 10,000 emails.

And so I think there's also a really interesting, one of the factors of cancel culture that I want to explore more, is the way that it's also radicalized public figures. Where part of being a public figure now, and this is totally new in human history, is this two way-communication between yourself and your audience. So if you're an Instagram influencer or a YouTuber, people can DM you, people can leave comments on your videos, people can be in your Twitter mentions. We've never had people who were famous as like PewDiePie or somebody, who can actually speak both ways with their audience, and can get feedback of everything that they do. Everyone is going to have a piece of feedback for you. It's so easy to get in touch with these kinds of public figures.

A lot of public figures get very limited negative feedback, but that also starts to radicalize them. It makes them feel like, "Oh, why can't people stop complaining?" One of the things about being a public figure, you do, I'm sure you get these emails too, but you get these emails that are completely wild. That's like, "You shouldn't say this word." Or I got an email the other day saying that I shouldn't use the word, "Ecosystem," anymore because ... I literally don't even know what the thing is, but you get these emails.

But they don't represent anything. If you have a large audience, some percentage of emails you get, are going to be wacky or in bad faith, or they haven't really listened all that closely to your work, so they're just making accusations against you that are just straight-up incorrect. But I think for public figures that can have a radicalizing effect, that you start to hate the ether out there. Every time you put anything out into the world, you get this bile back at you, and it starts to make you feel like, "Oh, fuck these people." And then this is where you get these YouTubers and other internet celebrities that spend a lot of their time responding to bad faith criticism online. Which, it's understandable to me that people would do that because it's frustrating. But it's also just, I don't think humans are designed to get this much feedback on our work.

Michael’s point about getting 10,000 angry emails or 10,000 negative reviews has stuck with me. 10,000 emails telling you that you’re bad at what you do may only represent 1% of your audience (in Michael’s case), and even if all but just a fraction of that 1% is respectful with their criticism, it’s still just too much for your average person to handle. The sheer volume is enough to kick you into flight-or-fight mode, and it becomes almost impossible to sort the legitimate questions and criticism from the people who just want to pile on. As Michael said, “I don’t think humans are designed to get this much feedback on our work.”

Imagine getting 10,000 emails in response to something you wrote or something you said. Even if you spent just 10 seconds on each email, it would take you nearly 28 hours to go through them all. And again, if you’re someone like Michael, whose work gets heard by as many as a million people, it only takes 1% of the audience to wreck you like that.

There’s a lot of profit in pain, and that’s a big part of the problem.

None of this is to say that people should stop offering criticism, but rather, to understand that 1,000 or 10,000 comments/replies/emails/reviews/etc. can build up and become overwhelming. And even more than that, there’s actually a pretty powerful incentive structure on social media to dump all over others which only encourages even more people to join in. Mallorie briefly mentioned this in her comic in reference to people who made YouTube content centered on criticism of her and her work.

This is the same exact thing that happened to my friend Franchesca Ramsey, who essentially stopped making content on YouTube after right-wing reactions to her videos became their own little cottage industry. As she said in an interview I did with her earlier in the year:

And so when my content started taking off, a number of people realized, oh, I can just react to this and piggyback off of the views and saying incendiary things will always get you views just saying something heinous, even if you don't believe it, because honestly, I'm not sure some of these people even really believe the stuff they're saying, not that that excuses it, but just say something wild or racist or sexist or transphobic or whatever, and you will rack up views.

So a lot of people did that. I paid a lot of people's rent for many years.

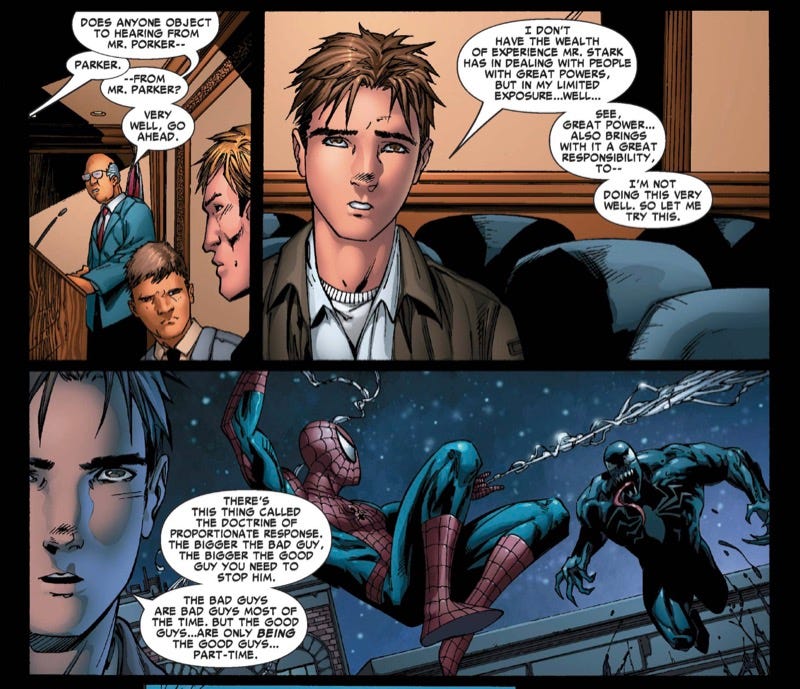

And, as happens so very often with me, it reminded me a bit of something I read in a comic book. In The Amazing Spider-Man #530, part of the “The Road to Civil War” series back in 2006, our boy Peter Parker testifies before Congress about the proposed Superhuman Registration Act which would require heroes to register their identities with the government. There, he references something called the doctrine of proportionate response.

I’m not saying that content creators are equivalent to villains (or superheroes), and I’m not saying their critics are superheroes (or villains, for that matter). What I am saying is that it’s worth considering whether or not the responses to online wrongdoings are actually proportionate. A lot of the time, they’re just not. Any individual response might be appropriate, but when combined together to crush an “enemy,” a “bad guy,” you end up with a full Avengers-level reaction to a local bike thief’s actions.

This relates to something I wrote in 2018 about how people with gigantic Twitter followings can intentionally or inadvertently start pile-ons in motion. (The context of the piece was that Elon Musk responded to a science journalist on Twitter, his tens of millions of followers took note, and made that journalist’s life a living hell for a little while. Author Neil Gaiman criticized Musk’s approach.) From my piece:

A common criticism, as posed to Gaiman, is that suggesting people take into account how their followers might react to something is tantamount to being forced to give up "free speech." What this fails to examine is how the fear that posting criticism of the president or a billionaire CEO will result in days of harassment might also have a chilling effect on "free speech" as a concept.

Social media also has a flattening effect in which people see someone like Trump singling out a family who criticized him as him just pushing back — failing to take into account that he is the president of the United States (and before that, a candidate for president and business tycoon).

These types of power dynamics exist everywhere, but we're usually able to navigate them a bit easier in the offline world.

For example, imagine you're at a baseball game and someone sitting in the row behind you deliberately spills a drink on your head. You might pop up ready for a fight, ready to get in their face. Now imagine the drink was spilled by a toddler. Would you still be ready to fight the toddler? Would you still get in the toddler's face? Probably not. This is because we all understand the importance of proportional responses. On the internet, this gets lost.

And while I don’t have millions of Twitter followers, I have more than a lot of people (247k-ish). I know that I’ve contributed to the problem with pile-ons throughout the years, I know that there are moments I could have/should have offered more grace and taken more generous readings of what people say, and I know that I need to do a better job of using what platform I have for good in the new year. I’ve been rude and angry and I’ve lashed out in the past. I’ve been part of the problem. More than that, I’ve been the problem.

No, I’m not saying to give people a pass for being unrepentantly sexist/racist/homophobic/transphobic/ableist/etc., but rather, that we at least consider what proportionate responses look like in these cases. Months later, should people still be slamming Mallorie for the shoplifting comic, especially after she clarified that it wasn’t a pro-shoplifting work? I don’t know, seems like that’s a pretty clear no. Should Lindsay’s criticism of Raya and the Last Dragon be something that follows her to the grave even though she elaborated on what she meant by it? I don’t know. None of that is up for me to decide.

The most popular Substacks seem to be dedicated to the art of the pile-on, the airing of grievances. Whether it’s a certain former New York Times opinion editor chasing the latest “campus controversy” story or a millionaire ex-pat lashing out at someone who annoyed him on Twitter that day, there’s big money in rage-y newsletters. And while I will absolutely use my newsletter to criticize people and views I take issue with, I don’t want to become one of the rage-based newsletters, even if it means I never make the type of money they do.

I’m going to be spending less time on social media in 2022. For my own mental health and for the hope of not further contributing to the oh-so addictive dunk-culture of the internet, I think this is important. I’m still trying to grow as a person, to find clarity and purpose in life, and so the best I can do is try my best and do it again the next day… and the day after that… and the day after that. 2021 was a very, very bad year for my mental health, and I’m determined to make 2022 a better one.

As always, thank you to everyone who subscribes to the newsletter. Whether free or paid, I appreciate the support all the same. And if you haven’t subscribed yet, I’d love it if you did now.

Warm New Year’s Wishes to All,

Parker

This is one of the best articles I have read in 2021. Count on me as a paid subscriber from this point forward. Happy New Year!

I'm definitely spending less time on social media next year as I finally quit Facebook earlier this month. I was on facebook largely to stay in touch with family, but in the Trumpist age too many of my family members fill me with rage.

I'm torn up by Lindsay Ellis's decision, but all I can do is wish her all the best. I could never thank her enough for her work. It's some of my all-time favorite youtubery.