Computer, Enhance

People keep running crime footage through AI thinking they’re helping. They’re not.

Nancy Guthrie, the 84-year-old mother of Today host Savannah Guthrie, was last seen at her home outside Tucson on the evening of January 31 and reported missing the next day. On February 10, the FBI released footage from a Nest doorbell camera showing a masked, armed figure at her front door the morning she disappeared. The footage is grainy and dark. The figure’s face is completely hidden behind a ski mask. There’s almost nothing to go on visually, which is probably why the FBI released it in the first place: they were hoping someone might recognize the build, the backpack, the way the person moved.

That’s not what happened.

What happened is that people on X immediately started running the footage through Grok (Elon Musk’s AI chatbot), asking it to remove the suspect’s mask and show them a face. Matt Wallace, a serial misinformation spreader on X, tweeted: “Hey @grok remove the kidnapper’s mask and show us what he looks like.” He shared the result and called it “better than nothing.”

But it’s not better than nothing. It’s worse than nothing. The face Grok produced isn’t a face it found under the mask. It’s a face it made up.

But Wallace wasn’t the only one. Scroll through FBI Director Kash Patel’s replies on X and you’ll find people demanding “enhanced” and “colorized” versions of the footage, plus AI-generated close-ups that supposedly reveal details invisible to the naked eye. One user was angry at law enforcement for not doing this themselves: “this entire video can be colorized. why hasn’t this been done?”

(Because it wouldn’t produce real information. That’s why.)

And then it got uglier. Someone asked Grok to put a keffiyeh on the suspect’s head. Grok did it. Other users dressed the suspect up as whatever type of person they’d already decided was guilty. Meanwhile, a completely fabricated “security footage” video claiming to show the moment Guthrie was taken went viral on Facebook before Lead Stories traced it back to a Vietnamese content-farm operation.

None of this helped find Nancy Guthrie. All of it made things worse for the people actually trying to find her.

Here’s the thing I keep coming back to, though: most of these people aren’t trolls. Wallace, sure. The keffiyeh guy, yeah, that’s just racism with a chatbot. But the person asking why the footage hasn’t been colorized? The ones posting Grok outputs and tagging the FBI? They think they’re doing something useful. They saw blurry footage of a crime, they had a tool on their phone that they’ve been told can do basically anything, and they tried to help.

The problem is that the tool can’t do what they think it can. And this isn’t the first time it’s happened. It isn’t even the fourth.

We’ve been trained to believe this works

If you’ve watched any crime procedural made in the last 30 years, you’ve seen the scene. A detective stares at a grainy surveillance image on a monitor. “Can you enhance that?” Someone clicks a button. The image sharpens. A face appears. The case cracks open.

It was always fake. Researchers who actually work in forensics call it “high-tech magic.” The gap between what CSI depicted and what crime labs could actually do got so wide that it earned its own name: the CSI effect. Jurors started expecting DNA results in every case. Prosecutors started running unnecessary tests just to have something to show the jury. One district attorney said in 2005 that jurors “expect us to have the most advanced technology possible, and they expect it to look like it does on television.”

That was more than twenty years ago, and the problem was TV. Now the problem is that generative AI looks like it actually delivers on the promise those shows made.

You give Grok a blurry surveillance still and ask it to enhance the image, and you get back something sharp and detailed. You ask it to remove a mask, and you get a face. A convincing face. A face with pores and stubble and a specific nose shape. And if you don’t understand how generative AI works (most people don’t, and why would they), it’s completely reasonable to look at that output and think: okay, so that’s the guy.

But it’s not the guy. It’s nobody. The AI didn’t find a face. It invented one.

Hany Farid, a UC Berkeley professor who specializes in digital forensics, put it plainly to NPR: “AI cannot figure out somebody’s identity when more than half their face is concealed. It’s hallucinating.” Researchers have known this for years. Even the earliest AI super-resolution systems, like one built at Duke University in 2018, couldn’t identify a specific face from a blurry image. The AI guesses what faces in general look like. Not that face. A face.

That distinction is everything, and almost nobody making these posts understands it. Enhancement (sharpening existing detail) and generation (creating new detail from scratch) are two completely different things. When you ask Grok to unmask a suspect, you’re not pulling hidden data out of the image. You’re asking the AI to imagine a person and draw them for you. The result is a portrait of someone who doesn’t exist, attached to a real crime, spreading across a platform where millions of people will see it and some of them will believe it.

Ben Colman, co-founder and CEO of Reality Defender, a company that detects deepfakes, told NBC News that these outputs are “crude approximations at best, complete fabrications at worst” and that they “do not accurately enhance or unmask individuals in the end.”

This keeps happening

September 10, 2025: Charlie Kirk. After Kirk was assassinated at Utah Valley University, the FBI released grainy security camera images of the suspect. Laura Loomer and others ran those images through Grok to “enhance” them. CBS News identified 10 posts where Grok had generated faces for the suspect before the actual shooter, Tyler Robinson, was publicly identified.

The AI-generated faces looked nothing like Robinson. They couldn’t, because they were invented. And when he was eventually arrested and his real photo circulated, conspiracy theorists pointed to the gap between the Grok face and the real face as proof that something was wrong. The AI images didn’t just fail to identify him. They became raw material for conspiracy theories.

January 7, 2026: Renee Good. An ICE agent, masked, shot and killed 37-year-old Renee Good on a Minneapolis street. Bystander video went viral. And within hours, users across X, Facebook, TikTok, Instagram, Threads, and Bluesky were running stills from the video through AI tools to “unmask” the shooter.

The AI gave them a face. The face came with a name: Steve Grove. It’s still not clear where the name originated, but by the next morning, at least two real people named Steve Grove were under attack. One was the CEO and publisher of the Minnesota Star Tribune, who had nothing to do with the shooting, ICE, or law enforcement in any capacity. The Star Tribune had to issue a public statement calling it a “coordinated online disinformation campaign.” The other was Steven Grove, owner of a gun shop in Springfield, Missouri, who woke up to find his Facebook page flooded with threats. “I never go by ‘Steve,’” he told the Springfield Daily Citizen. “And then, of course, I’m not in Minnesota. I don’t work for ICE, and I have, you know, 20 inches of hair on my head, but whatever.”

The actual shooter was later identified as Jonathan Ross. By the Star Tribune. Through court records. Traditional journalism, not AI.

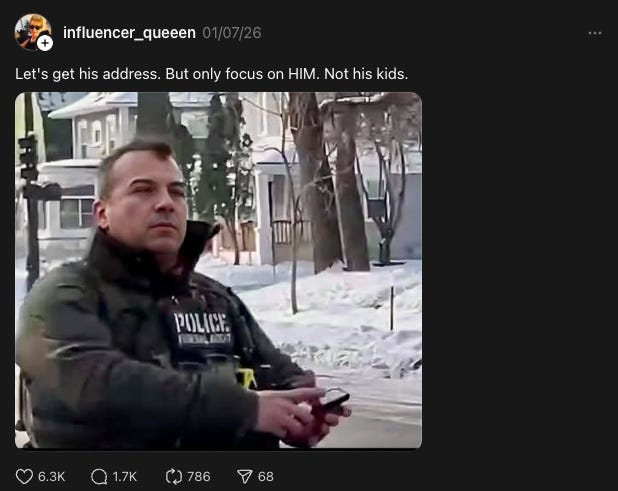

On Threads, one user posted an AI image of the agent and wrote: “Let’s get his address. But only focus on HIM. Not his kids.” That post got thousands of likes. The face in it belonged to nobody.

And then there was the user who took a screenshot of Good, dead in her car, and asked Grok to put her in a bikini. Grok did it. But that’s… part of a different story.

January 24, 2026: Alex Pretti. A Border Patrol agent shot and killed Pretti, an ICU nurse, on a Minneapolis street. Multiple bystander videos captured it. And the AI manipulation that followed was the worst yet.

One widely shared still showed Pretti collapsing as an officer behind him levels a weapon at his back. It looked damning and real. It was AI-manipulated. One detail stood out: the AI had rendered one of the officers without a head. Just gone. The AI couldn’t figure out what to do with that part of the image, so it deleted the person’s head, and the image still went viral because people weren’t looking at it that carefully. They were looking at the gun.

That specific image made it all the way to the United States Senate. Senator Dick Durbin held it up during a speech on the Senate floor, not realizing it had been manipulated. His office later told NBC News: “Staff didn’t realize until after the fact that the image had been slightly edited and regret that this mistake occurred.” (It wasn’t “slightly edited.” It was AI-generated fiction based loosely on a real photograph.)

On Facebook, an AI-generated video purporting to show an officer accidentally firing Pretti’s gun got 45 million views. The video’s creator labeled it “AI enhanced,” but Lead Stories’ fact-check made the distinction that matters: the tool didn’t just sharpen existing footage. It fabricated a muzzle flash, smoke, and sparks that don’t appear anywhere in the original video. That’s not simply “enhancement.”

Then MS NOW aired an AI-altered portrait of Pretti on television, on its website, and on YouTube. The image made Pretti’s shoulders appear broader, his skin more tanned, his nose less pronounced. A spokesperson told Snopes the network pulled the image from the internet without knowing someone had altered it.

And perhaps most dangerous: AI-altered images showed what appeared to be a gun in Pretti’s hand. Verified footage from multiple angles showed him holding a phone. The fake gun image was politically weaponized almost immediately.

The flood of AI content around the Pretti shooting also created a secondary problem. People started dismissing genuine bystander video as fake. Experts call this the liar’s dividend: once enough AI-generated content contaminates an event, bad actors can claim that real evidence is also fabricated. And once that happens, accountability becomes almost impossible. If any video can be waved away as AI, nothing can be proven to have happened the way it happened.

For those who would like to financially support The Present Age on a non-Substack platform, please be aware that I also publish these pieces to my Patreon.

It’s not just randos on X

It’s easy to read the cases above and conclude that social media users don’t know any better. But the institutions that are supposed to know better kept making the same mistake.

After the Kirk assassination, a sergeant with the Washington County Sheriff’s Office confirmed to KUTV that the county sheriff himself had posted a Grok-enhanced image of the suspect “in an attempt to be helpful.” They later added a disclaimer noting the image appeared to have been “denoised at a minimum.” It was generated by Grok. The watermark was visible in the image. After the Pretti shooting, Senator Durbin used one on the Senate floor. MS NOW broadcast one on television. None of them realized what they were sharing.

They all did the same thing the social media users did: they saw an image that looked real, they assumed it was real, and they shared it. The sheriff had the same instinct as many users on social media. He wanted to help. He had a tool. He used it. If the Washington County Sheriff’s Office can’t tell the difference between a real photograph and a Grok hallucination, why would we expect the average person scrolling X at midnight to do any better?

The Star Tribune’s own coverage of the Renee Good misinformation noted that false content “may be shared unwittingly by people with good intentions.” That framing is right, and it applies all the way up the chain. This is a literacy problem, not an intelligence problem. And nobody is teaching people to solve it. The pattern just keeps repeating, every few weeks, with a new crime and a new round of invented faces and new innocent people waking up to find the internet at their door.

What you’re looking at isn’t real

If you’ve made it this far and you’re someone who has done this, or thought about doing it, or shared an “enhanced” image without thinking too hard about where it came from: I’m not calling you stupid. The impulse to help when you see a crime is a good impulse. You see blurry footage of someone who hurt someone, and you want a clearer picture. You want to do something. I get it.

But every time someone does this, real people get hurt. A newspaper publisher in Minneapolis had to put out a statement defending himself against a mob. A gun shop owner in Missouri woke up to death threats. Conspiracy theorists used AI-generated faces to claim that the actual, arrested suspect in a murder case was the wrong guy.

The best thing you can do with crime scene footage is leave it alone. Send it to the FBI. Send it to local law enforcement. Send it to journalists. Don’t “enhance” it. Don’t “unmask” anyone. Don’t ask Grok to show you what’s under a mask, because Grok doesn’t know. Nobody knows. That’s the whole point of wearing a mask.

The next time you see someone posting an AI-generated face and saying “better than nothing,” understand that they’re wrong. It is worse than nothing. Nothing doesn’t get innocent people harassed. Nothing doesn’t give conspiracy theorists ammunition. Nothing doesn’t end up on the Senate floor.

What you’re looking at when you look at an AI-enhanced crime photo isn’t evidence. It’s fiction wearing the skin of a photograph. And every time it spreads, the actual truth gets a little harder to find.

I wish this post was popped up on everyone's social media apps every time they go to share any image or video! You're spot on, but I am pretty certain nearly all of your audience here already know... If only we had a well-funded education system in America, eh?