You (Yes, You) Should Start a Mailing List

If you're a journalist, author, artist, or anyone else who uses social media for business purposes, it doesn't hurt to start collecting people's email addresses.

Are you a current or former user of Twitter, Facebook, Instagram, or any other social networking platform? If you’re reading this newsletter, my hunch is your answer is "yes." If so, this pre-July 4th edition of the newsletter is just for you.

The tl;dr of today’s newsletter is that you should consider starting a mailing list, even if you don’t have any intention of starting your own newsletter. You can do this on Substack1 by clicking the button below this paragraph, or you can use a different service (you could do this with a simple Google Form).

Below, I’ll explain why you should do this, and I’ll also provide a bit of my personal history with newsletters/mailing lists.

This past weekend, Twitter introduced some bizarre new restrictions, seemingly attempting to isolate itself from the wider internet. Glancing over at Bluesky, I noticed several writers expressing their frustrations, rightfully distressed about the continued degradation of a platform that has served, for some, as the foundation of their careers.

In one Bluesky post, writer Nylah Burton wrote, “I’m worried that my freelance writing career is going to collapse without Twitter,” and asked editors looking for writers to reach out to her.

In another, writer Byron C. Clark wrote that had Musk’s Twitter takeover happened a year earlier, he “almost certainly” wouldn’t have become a best-selling author, and added, “Twitter shadowbanning Substack links has made continuing a journalism career difficult since then.”

I get it, I hear it, and I share the frustration and anguish of other writers. At one point, I had more than 250,000 Twitter followers, and the platform played a big role in helping me launch and boost my writing career.

A mailing list as a lifeline.

A few years ago, I started to get worried about what would happen to my career if one day Twitter disappeared, if the list of 250,000 people who had signed up to see my posts and links to my work suddenly evaporated, if I was stuck back at square one. After all, I didn’t (and still don’t) have much of a following on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, or LinkedIn (but feel free to follow me on those if you’d like). Could the bottom just drop out?

I started a mailing list and casually dropped links to it in tweets and other posts. I wasn’t planning on starting a newsletter, as I was working at Media Matters and getting ready to cover the 2020 presidential election, but I thought to myself, “Hey, it might not be the worst idea in the world to make some contingency plans in the event of social media chaos.”

In February 2020, Republican mega-donor Paul Singer bought a “sizable stake” in Twitter. You may know Singer, more recently, as Supreme Court Justice Samuel Alito’s billionaire sugar daddy. At the time of his Twitter investment, Bloomberg News reported that Singer and his company, Elliott Management, planned “to push for changes at the social media company, including replacing Chief Executive Officer Jack Dorsey.”

A lot of the reporting on Singer’s Twitter investment focused on how this could affect the company’s finances. I was more concerned about what could happen if Singer or another wealthy conservative tried to push the platform to the right, turning it into a firehose of right-wing content while suppressing progressive voices2. (Yashar Ali can vouch for this, as I texted him the morning I saw the story.) That motivated me to up my mailing list collection habits.

By the time I launched The Present Age in June 2021, I already had more than 1,000 emails on my list. Being able to start with that 1,000-user cushion helped as I ventured out into the world of self-employment, but would have remained just as useful had I continued working at Media Matters or anywhere else.

As of this morning, I have 33,347 free subscribers to this newsletter. Is it 250,000? No, but it’s something, and with the way Twitter has been going the past year or so, I’ll take it.

Most social media platforms box you in, tying you to the whims of investors and the occasional Elon Musk-sized wrecking ball.

Back in January, I wrote about “enshittification,” a term coined by Cory Doctorow and written about in a brilliant piece on his Pluralistic blog.

The general idea is that every platform — whether it’s Twitter, Facebook, YouTube, Amazon, or TikTok — begins as a place that is good to its users. Over time, those platforms shift to a strategy of maximizing value for their business partners before ultimately maximizing their own profits at the expense of both users and business partners. Again, I highly recommend checking out Doctorow’s piece on this.

Since taking control of Twitter, Elon Musk has enshittified the platform in more ways than I can list, crushing the things that users liked about it (being able to follow breaking news events and seeing updates from trusted sources) and inventing new ways to make the product worse (prioritizing tweets from paid subscribers over subject matter experts, eliminating the verification process, and limiting the number of tweets you can look at per day). Still, people feel tied to Twitter because that’s where their followers are. The cost of ditching Twitter entirely and rebuilding your promotion feed is high, and it’s what’s keeping a lot of people who otherwise would have told Musk to shove it busily posting away.

Doctorow elaborated on this in another great piece, this one published by Locus (bolded emphasis mine):

When economists and sociologists theorize about social media, they emphasize ‘‘network effects.’’ A system has ‘‘network effects’’ if it gets more valuable as more people use it. You joined Facebook because you valued the company of the people who were already using it; once you joined, other people joined to hang out with you.

Network effects are powerful drivers of rapid growth. They’re a positive feedback loop, a flywheel that gets faster and faster.

But network effects cut both ways. If a system gets more valuable as it attracts more users, it also gets less valuable as it sheds users. The less valuable a system is to you, the easier it is to leave.

When you leave a system, you have to endure ‘‘switching costs’’ – everything you give up when you change products, services, or habits. Quitting smoking means enduring not just the high switching cost of nicotine withdrawal, but also contending with the painful switching costs of giving up the social camaraderie of the smoking area, the friends you’ve made there, and the friends you might make there in the future.

For social media, the biggest switching cost isn’t learning the ins and outs of a new app or generating a new password: it’s the communities, family members, friends, and customers you lose when you switch away. Leaving aside the complexity of adding friends back in on a new service, there’s the even harder business of getting all those people to leave at the same time as you and go to the same place.

Each commercial social media service has two imperatives: first, to make it as easy as possible to switch to their service, and second, to make it as hard as possible to leave. When Facebook opened up to the general public — and not just university students — it needed a plan to deal with MySpace.

At the time, MySpace was the largest social network the world had ever seen. It was overly complex, filled with spam, and often joyless, but for MySpace users, it had a major advantage over Facebook: all their friends were already on MySpace.

It didn’t matter that Facebook had a better user interface and more features. It didn’t matter that Facebook promised not to spy on its users on behalf of advertisers (yes, this was Facebook’s pitch in 2006 when it dropped the requirement that you sign up with a .edu address).

Facebook addressed this problem by giving MySpace users who switched to Facebook a bridge between the two services. Simply give this tool your MySpace login and password, and it would use a bot to login to your MySpace account, scrape all the waiting messages in your queues and inbox, and push them into your Facebook feed. You could reply to these, and the bot would log back into MySpace and post those replies as you.

Facebook attacked MySpace’s high switching costs head on, lowering them for users and unleashing network effects and rapid growth.

But as Facebook and Twitter cemented their dominance, they steadily changed their services to capture more and more of the value that their users generated for them. At first, the companies shifted value from users to advertisers: engaging in more surveillance to enable finer-grained targeting and offering more intrusive forms of advertising that would fetch high prices from advertisers.

This enshittification was made possible by high switching costs.

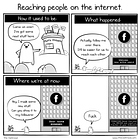

This is where we’re at with Twitter, but it’s happened to every centralized platform over the years. As user numbers go up, the incentives to actually do right by those users go down.

Setting up a mailing list is a good way to say, “Hey, if anything should ever happen to [social media platform], please sign up for my mailing list so I can keep in touch with you and share updates on my work.” It’s a helpful way to avoid losing all the relationships you've built over the years.

Decentralized social networks help address the problem of high switching costs.

If you want to leave Twitter, you can’t just pick up and move your Twitter followers over to Facebook; you have to rebuild the follow list. The promise of decentralization (I’m a tech novice, so I’m sorry if I fail to clearly explain this) is that you should be able to bounce from one decentralized network to another with minimal friction.

Bluesky and Mastodon are (or, in Bluesky’s case, will be) examples of decentralized,3 federated social networking sites. Bluesky engineer Paul Frazee recently shared a thread explaining why he’s so committed to protocols and decentralization:

Products get detached from their users as they settle into being businesses. They start looking for ways to cut costs and extract revenue. This often means losing interest in the day-to-day experiences of their communities. It’s a precarious situation.

We want to do right by yall, and that means being forward-looking. Our culture doc includes the phrase “The company is a future adversary” to remind us that we won’t always be at the helm — or at our best — and that we should always give people a safe exit from our company.

It’s weird at times to frame our priorities as protecting users from us, but that’s exactly what we’re trying to do. The Bluesky team is made up of users. None of us come from big tech companies.

We all came together because we were frustrated by the experience of feeling helpless about how our online communities were being run. We don’t want to give that same feeling to other people now that we’re the builders.

When we build an open protocol, we’re giving out the building blocks. We want to start from the premise that we’re not always right or best, that when we are right or best then it might not last, and that communities should be empowered to build away from us.

Sometimes this can all feel very intangible and abstract, and for the average user the goal is to just feel like a good & usable network. But this is one big reason why we put all the Fancy Technology under the hood.

I think that’s a great strategy, and I’m cautiously optimistic about what decentralization can mean. It just doesn’t do anything to help with the current problems of having large followings on deeply enshittified platforms like Twitter and Facebook. That’s why I recommend, again, starting a mailing list as a lifeline to your social media mutuals.

That’s all for me today. Have a safe 4th of July, everyone.

Parker

You can always use Substack to generate the mailing list, then export it and take it to a different mailing list/newsletter platform if you decide you want to start up on Constant Contact, MailChimp, Ghost, etc.

And it’s not like Twitter was some sort of lefty paradise under Dorsey’s leadership. He regularly palled around with right-wing figures like Ali Alexander, rushed to the defense of Candace Owens after the site accurately referred to her as a “far-right” commentator, and held off enforcing policies to ban white nationalists for fear that Republican politicians might “accidentally” get flagged. Dorsey is and always has been bad news, but the onslaught of baseless right-wing cries of “anti-conservative bias” were getting leadership to push the platform further to the right, bit by bit. Singer’s involvement worried me that this would accelerate.

Mastodon and Bluesky are federated networks. Some will (correctly) argue that they’re not yet truly decentralized. The Bluesky network is built on the AT Protocol, which will someday allow users to keep their contacts if they move from Bluesky to another competing instance (currently, Bluesky is the only available instance on the AT Protocol, but that will change). The point is that the switching costs go way, way down with the ability to pick up and move to different networks. Bluesky is still in beta, so it’s pretty limited.

Goddammit I appreciate you. You're so fucking smart, P, and you use your knowledge to help others. Is this gross to put on main? Yes, whatever, I'm being sincere about a friend, it's fine, I'm FINE.

Cory Doctorow has a book coming out soon (The Internet Con) that I got an ARC of -- it follows up further on the switching costs argument and is extremely persuasive!

When I first heard Musk was buying Twitter, I made a point of signing up for as many mailing lists from smart people as I could, knowing that if I deleted Twitter (which I did back in October), it would be a way to keep the network once the dust settles. Glad I did!